After what has been a progressively uncomfortable year, I have both pleasure and relief in revealing a painting which has been the product of much thought, deliberation and soul-searching in the quest for a meaningful direction for my future: I take pleasure because the painting is almost finished, and relief because it seems to have been successful, at least as far as I had intended it to be.

A year ago I had an interesting discussion with a collector in New York who lamented his lack of wall space as hinderance to enlarging his erudite collection. Perhaps cheekily I had suggested that he had unadorned ceilings which could be employed to display works of art in the eighteenth century manner, in keeping with his collection of European paintings of the period. The resulting conversation concluded with a commission for me to undertake such a painting, in watercolour and on a significant scale. This would be a first, both for watercolour and for contemporary art. It would be new ground for me: I relished the idea and rushed off to Italy to consult the masters of the settecento.

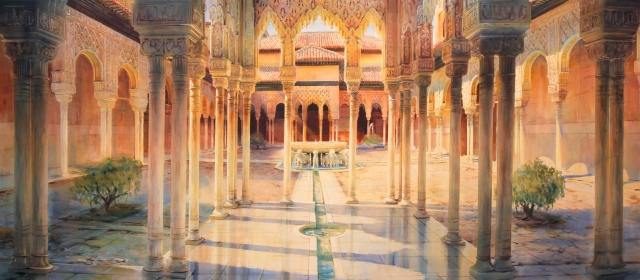

In the first instance this picture – now almost completed – represents a new horizon for me, perversely for the simple reason that it has no horizon. Being a view upwards though an imaginary roof to an infinite sky, it has a perspective which relies on the third dimension of the vertical, a perspective cut free from the merely terrestrial. Secondly this view has no subject as such, no representation of reality other than the sky and sunlight above an invented architecture which departs from the observance of reality. Thirdly, and importantly for me, this view is not factually representational but borrowed in part from history, then adapted and invented. Fictitious in this architectural tableau is the population of what appear to be ghosts whose only function is to represent those tenets and disciplines of life which we, the viewers, might have taken for granted: faith, toil, sagacity and fecundity – in common parlance: confidence, hard work, knowledge and productivity.

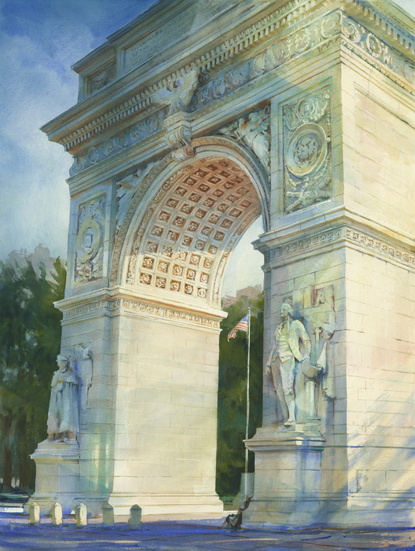

But what is the purpose of this painting, I hear the muttered question tinged with cynicism? Well, I’ve been loyal to the representational for most of my painting life, faithful to place and light, to truth and to the actuality of the subject. Occasionally however the truth is awkward or uncomfortable. During my career I have painted beauty, elegance and grace in architecture. I have also painted fate as manifest in the destruction and neglect of ruins. Sometimes the inspiration comes from unlikely quarters: over the past year my path ahead has been at times tangled and obstructed, calling for diversion and courage, flavoured with sadness and reflection – a landscape of Dante as I am reminded. With encouragement I found the leap from the familiar to the unknown in this work to be daunting and yet inspirational. It required courage in the confrontation of possible – or probable – failure. Rather like leaping from a runaway train, escape was the principal motivation behind this painting.

Although not quite finished, today we installed this painting in the ceiling of my studio, in a proper place to test its efficacity before the final details are elaborated in preparation for its dispatch.

Some remarkable things revealed themselves: floating overhead the picture morphed into a completely fresh image, unencumbered by accuracy and correctness. Let me explain: we are accustomed to the terrestrial world with a horizon, we gape up at skyscrapers in Manhattan or peer down into the Grand Canyon, but from the safety of our horizon-based world – terra-firma. Everything is related to the horizon, our level, our balance. We might look out of the window of an aircraft at 35,000 feet but always with the horizon to give us a fixed point: remove that horizon and we suffer from vertigo, dizziness and disorientation. Looking up at a ceiling painting we can feel the ability to fly into it and soar like a bird, freely but with our feet still firmly on the ground.

Given freedom from our earthbound horizons we loosen our reliance on accuracy and on truth. We can twist and turn to look at this view from varying angles without questioning, simply enjoying the gift of flight, at least momentarily. We are looking at a picture which is not a view in the conventional sense, more of a virtual reality which we can enjoy without cynicism, not requiring the affirmation of being ‘correct’. As a representational painter I find this departure very exciting.

So what of this image on the ceiling? At worst it’ll be a talking point, a curiosity: maybe it’ll challenge the condemnation of representational art as somehow shallow and passé. Maybe it’ll start a trend. I would hope it might encourage other enlightened patrons to ask me to do more, far larger ceilings to be installed in places where they can be seen by the world.

•

Under the archway furthest from the sun in the painting, a cartouche bears the following inscription:

“Beviamo profondamente dal pozzo della tradizione e nutriremo l’arte del futuro”

(tr. “We drink from the well of tradition to nourish the art of tomorrow”)

The sentiment is entirely mine and the observant viewer may recognise a veiled reference to Andrea Pozzo whose huge fresco ‘The Apotheosis of S Ignazio’ adorns the nave vault of a church close by the Pantheon in Rome, which provided me with the inspiration and model for this painting, together with the courage even to imagine that I could actually achieve it.

•

I would be delighted if you forward this to anyone who would value the message or who might simply enjoy the painting.

With best wishes for a very Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year, and many thanks to those who have encouraged me through a difficult year.

Alexander Creswell, Christmas 2014